Nature’s Nation – An Eco-Critique of American Art

By Margaret H. Adams

There might be no better stop for the traveling exhibition Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment than at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, a museum that in many ways became a catalyst for the rapidly developing landscape in Northwest Arkansas. The exhibition approaches three centuries of the United States’ artistic production with eco-criticism, the interdisciplinary field that frames critical and analytical work through social, economic, and political relationships with the environment. Overall, the show succeeds in unearthing marginalized identities and narratives previously left out of significant art historical discussions but seems to lose a critical cohesiveness as the show’s discussion ventures into the contemporary moment.

Organized by Alan C. Braddock, Ralph H. Wark Associate Professor of Art History & American Studies at William & Mary, and Karl Kusserow, the John Wilmerding Curator of American Art at Princeton University Art Museum, Nature’s Nation chronicles the role of nature on the American psyche, ultimately exposing social and environmental realities buried under the idea of national exceptionalism. The exhibiting collection shows an impressive 120 works and includes colonial portraits, landscape paintings, indigenous handmade works, eighteenth century silver objects, modernist photography, and contemporary activist artworks. The show makes its strongest cases with nineteenth century works, presenting on how major U.S. events have been historicized visually, often to manipulated effect that constructs varied yet contradictory depictions of the country’s relationship with nature. Thematic galleries illuminate American phenomena such as the extinction of the American Buffalo, the Industrial Revolution, the Civil War, slavery, Manifest Destiny, and deforestation.

The first two galleries, “The Order of Things” and “Dying Words: Extinction,” are a strong introduction to the exhibition’s scope, showcasing works from over five hundred years of artists side by side. Notably, the first two works of the show, created over 130 years apart, speak directly to the current environmental crisis. Albert Bierstadt’s Bridal Veil Falls, Yosemite (1871-1873) hangs next to Valerie Hegarty’s 2007 work Fallen Bierstadt, a ruined and collapsed version of its nineteenth century counterpart. In this comparison, Hegarty’s work shows Bierstadt’s image, though beautiful and captivating, to be unsustainable in artistic practice, as well as in the nation’s treatment of the natural landscape.

Throughout these early galleries, the artworks showcase their subjects through a scientific and at times taxonomic lens, evocative of the way in which museums categorize artists and genres of art. Works include Charles Willson Peale’s The Artist in His Museum (1822) Mark Dion’s Scala Naturae (1994), John James Audubon’s Carolina Parakeet (Parrot) (1827-1838), and Maya Lin’s What’s Missing? (2010), an interactive website that archives the disappearance of various flora and fauna on a world map. Following these two galleries the exhibition falls into a loose chronological order, exploring major themes and historical phenomena.

Left: Valerie Hegarty, Fallen Bierstadt, 2007, foamcore, paint, paper, glue, gel medium, canvas, wire, wood. Right: Albert Bierdstadt, Bridal Veil Falls, Yosemite, 1871-1873, oil on canvas.

In the gallery “Building the View,” landscape artists like Thomas Cole and Thomas Moran, both from the Hudson River School, idealize man’s relationship with nature. At the time, the national identity became so intertwined with the concept of nature that the work of landscape painters promoted the continued sense of urgency and belief in Westward Expansion. Paradoxically, the depiction of harmonious, pastoral landscapes where humans and nature seamlessly mingle became the very force behind the land’s exploitation. Historically, land ownership was for the elite, white, male population, and the ecological damage from land development coincides with patterns of racial, gender, and class inequality, as seen in the dialogue created between Thomas Cole’s pastoral cottage scene Home in the Woods (1847) and Alan Michelson’s three-dimensional replica of Cole’s cottage in Home in the Wilderness (2012).

Thomas Cole, Home in the Woods, 1847, oil on canvas.

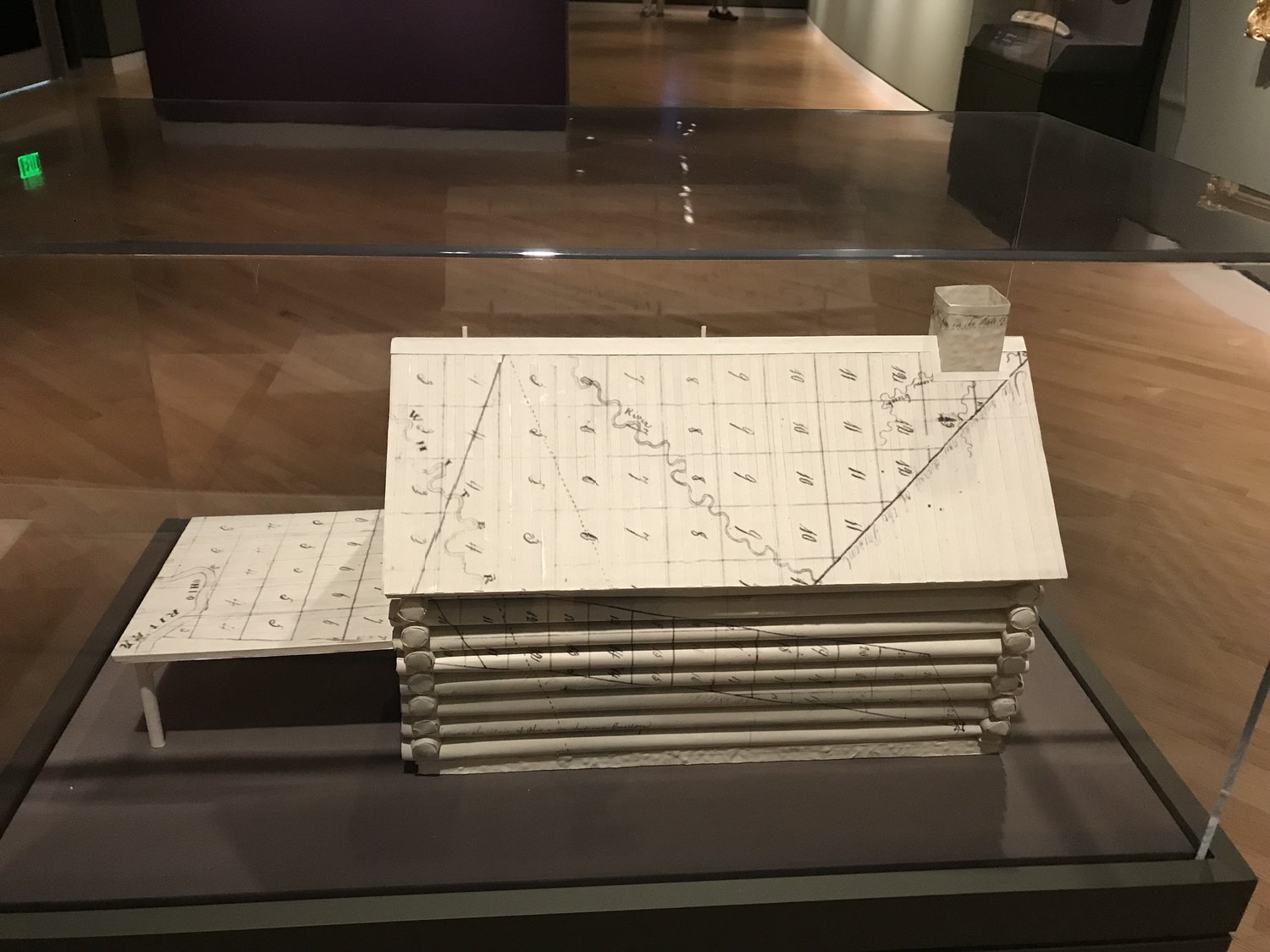

Thomas Cole’s Home in the Woods (1847) shows a depiction of the artist’s own home in the Catskills mountains. All around the cabin are the vestiges of the day’s chores–the laundry is hung on the line, the dishes are laid out to dry, an axe is left in the stump of a fallen tree–small signs that the untouched land is slowly being altered by man. Contrastingly, Alan Michelson’s Home in the Wilderness (2012), shown next to Cole’s image, is a re-constructed model of Cole’s cabin made of paper from the 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne, a document that pushed the native population out of three million acres of Indian Territory–a reality that Cole’s painting excludes. Michelson’s critique of cultural displacement starkly contrasts Cole’s image and further drives home the role of contemporary artists in critiquing the negligent quality of US history.

Seeing the first half of the gallery unfold these complex dialogues in this way suggests that the exhibition’s course will inevitably end with Contemporary artists and a conversation on the role of art in the contentious environmental moment in which we are currently living. However, this expectation was never met fully, as the modern and contemporary galleries were confusing at times. The later part of the exhibition starts a critical dialogue on pioneering twentieth and twenty-first century artists but ultimately need a clear definition of eco-criticism in the contemporary moment.

The early twentieth century gallery titled “Natures’ Vital Forms” loses the cultural and social application of artworks seen in the rest of the show in exchange of a formalist approach. Although the works in this gallery reflect the artistic shift that favored innovation and experimentation in place of naturalistic depictions of the world, this gallery is confusing. I feel there are more relevant ways to highlight seminal artists like Georgia O’Keefe and Frank Lloyd Wright that can focus on the artists’ relationships with nature rather than design. Additionally, perhaps not every exhibition that shows twentieth century artists needs to include Jackson Pollock. It felt as though this section was more of a distraction than a lead-in to the last galleries, titled “Aesthetics of Destruction” and “The Changing Planet.” These final rooms offer stunning works focused on environmental and social justice, raising questions of art’s ability to activate criticism locally and globally.

Alan Michelson, Home in the Wilderness, 2012, handmade paper, archival ink, and archival board.

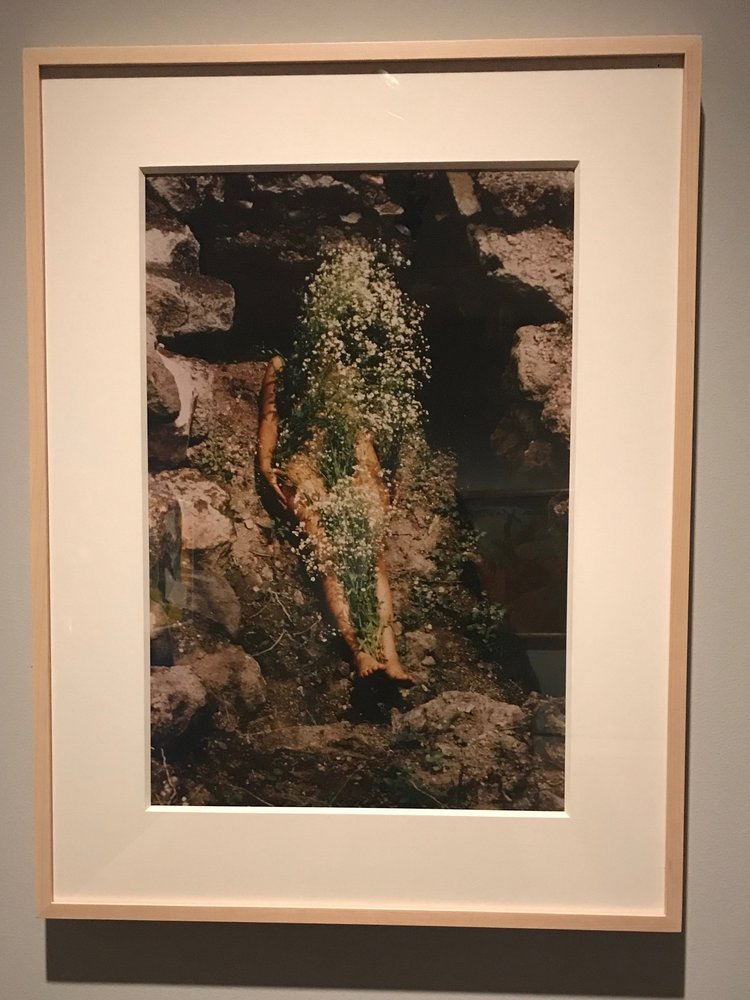

Of particular importance is Robert Smithson’s Bingham Copper Mining Pit, Utah Reclamation Project (1979), a project on reclaiming industrialized landscapes. Smithson was a seminal Land artist that significantly influenced the eco-critical art movement. Although Bingham was never fully realized before his death in 1973, the work shows a practical application for art to rectify local and global issues. More contemporary works like Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s Browning of America (2000) and Cannupa Hanska Luger’s Mirror Shields (2016) feature art’s capacity to claim a voice for indigenous minorities in the US. It is refreshing to see artists like Allora & Calzadilla and Ana Mendieta in the final galleries, as their works often are explored in relation to Latin America or Central America. The inclusion of these artists in the show signifies that the term ‘nation’ is changing to embrace the diverse influences of spreading information, technologies, and cultures.

National borders are not inherent to the natural landscape, but instead are manmade and exclusionary. The environmental laws passed by one country has an effect on the rest of the global environmental condition. Expanding the idea of the environment would include a damning investigation of the gentrification of urban America, the continued process of obscuring and demolishing cultural histories, the torture and abuse of animals in an unsustainable food system, the economic discrimination of public transportation, a capitalist blind-eye to preservation and conservation, and many other environmental concerns that extend far beyond our often filtered lives where the environment is anywhere but here. I just don’t see these issues pushed in those last moments of the show, although the artworks demand that attention.

Robert Smithson, Bingham Copper Mining Pit, Utah Reclamation Project, 1973, wax pencil and tape on plastic overlay on photograph.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled: Silueta Series, Mexico, 1973-1977, color photograph.

Interestingly, Crystal Bridges’ installation of Nature’s Nation, curated by Mindy Besaw, offers viewers a transparent run-down of the world of art institutions. Wall text explains the material and fabrication of ornamental curtains and wood-cut signs found at the beginning of each main gallery. Two interactive screens show viewers the museum’s operational expenses and the exhibition’s production costs, including temperature regulated trucks, catalogue production, and painting materials. Architecturally speaking, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art–an institution built into the seemingly natural countryside, complete with a manmade pond and paved walking trails–reflects the sentiment of the altered landscapes found in the exhibition’s works.

Nature’s Nation is part of progressive scholarship that seeks to re-open the historical narratives seen in art works, making it an essential exhibition for the discipline of art history and to our local area today. As Northwest Arkansas continues to undergo major changes, it likely will not resemble the rural area that many of us have a deep-seated affection for. It’s curious to consider the consequential issues from this development in aspects like employment, the housing market, poverty, education, health care, and public transportation through the same lens we’re given in Nature’s Nation. It isn’t that any of this development and wealth is inherently bad for our area or for the progression of America, but perhaps the ongoing problem which the exhibition seeks to showcase in its sweeping review is that we can’t see the forest for the trees.

Cannupa Hanska Luger, Mirror Shields, 2016, masonite board, mylar adhesive paper, and rope.

Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment is at Crystal Bridges American Art Museum until September 9, 2019.

Images provided by author.

*Cover image: Postcommodity, Repellent Fence, 2015, land art installation and community engagement (Earth, cinder block, para-cord, pvc spheres, helium), photo by Michael Lundgren