Stephanie explains her work Myspace, Oil and spray paint on unstretched canvas, 5’x7′, 2017. Hung at Ozark Beer Company, Fall 2021.

Stephanie on the bed in her house. Aspects like the crochet bedding as well as an earlier painting of a dollhouse point to her work’s continued focus on aspects of the domestic space.

This interview ends with four women—several that had just met or started talking in earnest that night—sitting on the ground outside of Stephanie Petet’s home studio. It was an early fall evening, and we were continuously flailing our arms at the motion sensor to keep the garage light lit as we candidly and passionately talked about Northwest Arkansas music and art, and dreamt up events to highlight artists we loved.

This breakdown of formal “interview” boundaries emanated from the creative process of Stephanie herself, who forms a purposefully anti-establishment, open, and ritualistic routine of making, from the private and internal into the shared and public. Thus, starting at this moment of shared connection, gets us in many ways to the heart of Stephanie’s creative endeavors and the winding path she took to the unapologetic work she makes today. Her paintings by necessity represent a continual reworking of her progress, an infinite layering of palimpsests, at once ebbing and flowing, starkly clashing and melding together.

I first met Stephanie almost a decade ago as a young woman fresh out of art school at the University of Arkansas. At the time, she was just kicking off the band Witchsister with her younger sisters and cousin. Witchsister is a hard-hitting, loud, and fun reminder of women’s power in a male-dominated industry, but many who see them perform may not realize that Stephanie is also prolific painter who is constantly experimenting, infusing spatial problems and physiological experiences in her abstracted landscapes which are vaguely nostalgic, comforting, dream-like, and unsettled. In many ways, her painting and her music have entwined into symbiotic parts of her being, and she embraces both of these art forms as integral to who she is. Now in her early 30s, both known parameters and purposeful denial of art’s “rules” fuel a practice that is both solitary and pensive, while also being collaborative and supportive.

After graduating with her BFA, Stephanie kept her feet in both worlds of art and music. She taught high school art; spent years teaching guitar, vocals, and bass at School of Rock as Associate Music Director; put in a semester as a post-baccalaureate student; completed a residency at the Arts Students League in New York; and assisted on a mural at the Life is Beautiful festival in Las Vegas. She has installed at least one art show every year since 2008, including in 2021 at Mavis Wine Company and Ozark Beer Company in Rogers, where we at RRIP met her surrounded by her large-scale works on canvas, made mostly during the pandemic. It was during this tumultuous time that she “got serious as my new 30-year-old self and buckled down.” She says creating these became a “release because I wasn’t able to perform live music anymore, so I had to overproduce. It’s kind of outrageous sometimes how much I make. This year I’ve had more shows than I’ve had in my entire life.”

Stephanie with detail of Shadow Work – Venus, Mixed media on canvas, 6×9, 2021. Hung at Ozark Beer Company, Fall 2021.

As one of the most active artists and musicians in Northwest Arkansas, Stephanie attempts to stick to a rigid practice within designated rooms in her Fayetteville home. She relies on structure to hold herself accountable because “making work is part of my existence. It’s something I have to do every day.” Her routine of painting in the morning is wrapped up in the ritual of maintaining a mental health process. She works on multiple pieces at once as both an emotional and physical endeavor; “I know my process really well by now. I don’t even get in my head and ask if I want to do this anymore. It’s just a body response…. I want a couple canvases on deck just so they can sit there and annoy the hell out of me. They kind of talk back at me.”

Stephanie has long been playing with scale, form, color, and materials, but now her pieces declare a more purposeful statement. When she was a student, she had to make objects she was able to carry back and forth from her studio, and as an art teacher she worked on miniature collages to mirror her students’ projects. Now, working primarily at her home studio, she works with un-stretched drop cloths available at any home improvement store, creating wall hangings that change shape based on the location they are installed. She scribbles on canvases with oil pastels and choses colors that are vivid, striking, and clashing, like a slash of neon pink against pastoral blendings of greens. In school she learned to never use color straight from the tube, to always mix colors. But, now, she says “I will squeeze it straight out onto the canvas….I break all the rules constantly, which is what punk rock is—that’s rock and roll….I want my paintings to be punk.”

Stephanie with detail of Shadow Work – Venus, Mixed media on canvas, 6×9, 2021. Hung at Ozark Beer Company, Fall 2021.

Stephanie in front of: Hell River, Acrylic, spray paint, and oil pastel on unstretched canvas, 2021. Hung at Ozark Beer Company, Fall 2021.

This painted domestic space links her to her heritage—to the dream-like nostalgia she conjures within her scenes of bright pastels mixed with dark caverns, symbolic of working through her own past and bringing forth a psychological meaning beyond the formal qualities of the medium.” In these paintings, Stephanie has transitioned from using materials associated with “high art,” such as expensive oil paints, to what she can afford on limited funds. She uses household items like laundry baskets, six-pack holders, clothes hangers, and rubber bands to make stencils that allow her to create intriguing patterns with no direct reference. In her creative use of materials, she says she is “playing with the idea of craft, but in a formal setting that creates an atmosphere where people won’t know the process they are seeing unless they look closely.” Using do-it-yourself craftwork, she denies the viewer an understanding of process or labor which often gives “Craft” as a genre its legitimacy.

Stephanie shows off some of her horse-related objects which are often infused within her work.

Stephanie states that if she was in school, these actions and her process might be viewed as diluted from “pure” painting and bordering on “mixed media.” But to Stephanie, her process is vitally painting. These transformations in her work became an exuberant and supportive declaration that painters can evolve and grow in their work, particularly once they start modifying what they learned in formalized, often elite art schools in order to play by their own rules. “I’ve had to be really innovative after school which makes practicing harder,” she states, “But then, this becomes part of your process and even your own statement telling others you don’t have to spend all this money. If you feel creative, just do it.”

Stephanie’s scale of work has grown to the point that she is now interested in taking on mural projects. She had a rewarding experience over late summer 2021 completing a mural with local artist Roxy Erikson as assistants to Camille Walala at the Life is Beautiful festival in Las Vegas. Stephanie’s decision to combine her training with others’ directives on large, public installations forged new avenues for how her own painting could evolve. Mainly, Stephanie loved taking the solitary practice of working in a studio into an immersive environment on city streets. Doing so allowed her to talk to people, and have their opinions and experiences infused into her memories as she wrapped an old gas station in bright abstract patterns, polka dots, and stripes. She said it was one of the hardest experiences she’s had regarding labor, time constraints, weather conditions, and unknown variables, but also the most rewarding and exciting to her future plans.

These experiments into scale, color, form, and content represent Stephanie’s internal resolution between her music and her painting. Witchsister rehearses in Stephanie’s studio garage around the paintings she’s working on. This creates an informal, constant dialog between her and her bandmates. She only recently gave herself permission to be unapologetic about her painting in a way she already was with her band. “I’m straddling the middle of a fence where one side is music land and one side is art land. There are points in my life where I feel like I jumped over the fence, but I think that is society telling you that you have to choose, and I’m not going to pick a lane and isolate myself from so many opportunities. I’ve gotten to a point where I feel like the way I’m visually expressing is getting close to the way I’m musically expressing. The two practices are holding hands finally.”

Stephanie approaches Witchsister with the same intentions she brings to her paintings. Members of Witchsister know that they are one of the only—if not the only—active all-female bands in Northwest Arkansas. Given this responsibility, they hope to initiate more creative moments with other women and folks in the LGBTQAI+ community to infuse more variety and acceptance into the Northwest Arkansas arts scene. They want their performances to be intrinsically supportive and safe for those who might not feel this way otherwise. As Stephanie proclaims, “Our crowds are becoming increasingly young females, which, I’m like Thank God—I’m talking to you directly. That’s why I have to keep writing these songs—this loud, angry music—because I see that one twenty-year-old girl out in the audience that just needed someone to yell about it with her. I want to inspire that person and create a safe space for them. We need to all go out and make other bands with other females on purpose and share a cohort and collective. This is really important to give young females confidence to do what they need to do and express themselves and feel safe about it and not be interrupted by the male gaze.”

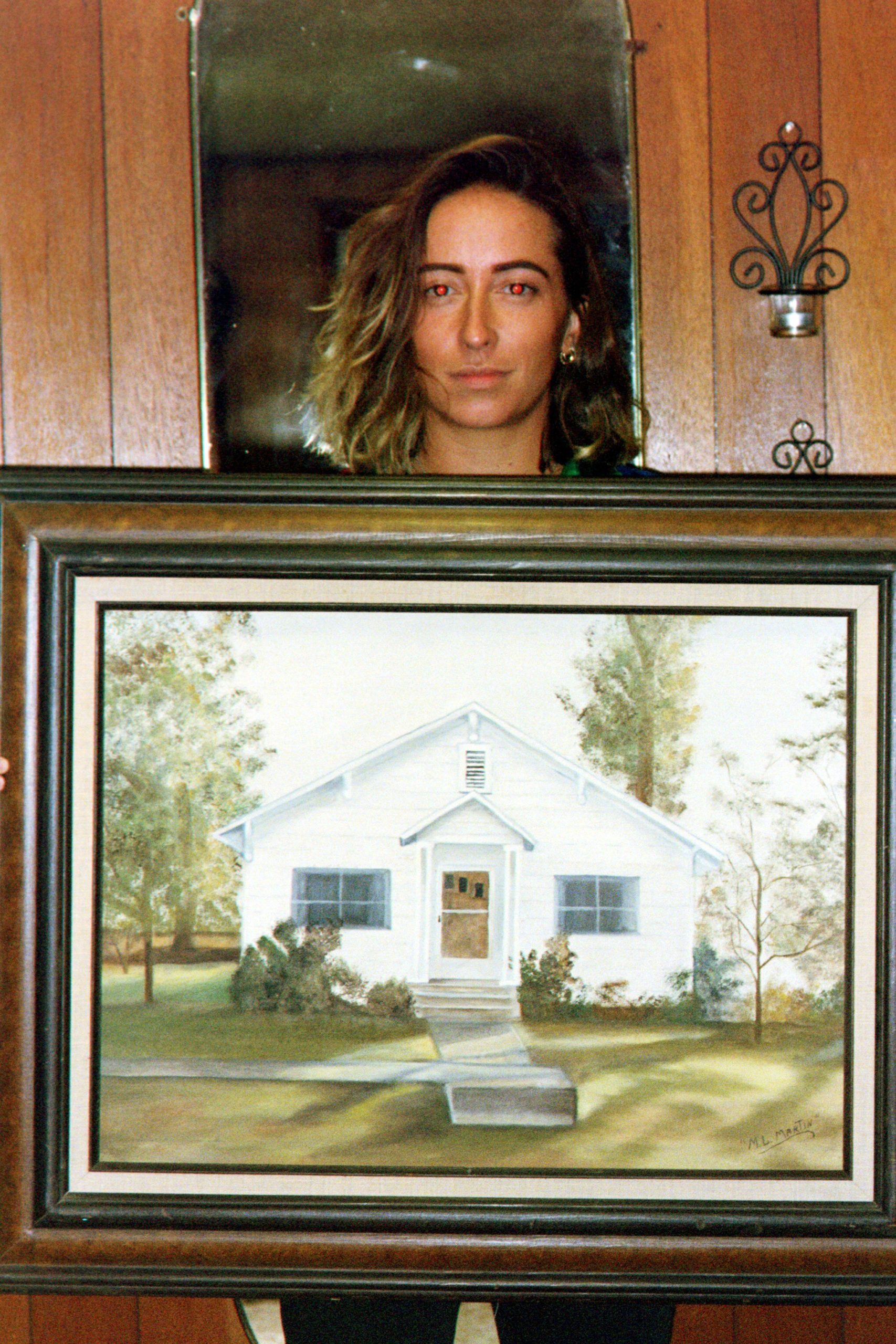

Stephanie holds a picture that hangs in her hallway of a house her grandmother painted, linking her family, passed-down objects, and an interest in domestic spaces within her work.

Stephanie’s hope of what she will be able to cultivate for others is exactly what the four of us experienced together during this interview. After we talked at Ozark, we viewed her house—almost a found object assemblage in its own right in regards to her influences and process. It is filled with her own work as a walk-through of her various styles from the past decade. One room consists of all of her smaller studies, mostly on paper, pinned salon style on every wall. There, I saw her ongoing fascination with houses, exterior scenes from windows, and objects that are just distorted enough in form, color, or scale not let the eye sit comfortably on one static, solid point of view in her final pieces. Many scenes from her final paintings were visible in pieces throughout—the bushes out her back yard, the horse window-hanging and spray-painted laundry baskets which she made stencils out of, and reminders of her own history with trinkets from her family. She points out a picture of a house hanging in the hallway her grandmother painted as specifically indicative of her lineage in art, landscape, and domestic space.

Outside in the garage at the end of the night, Stephanie held her own informal critique, asking us what we felt about her most recent work in progress and what we think art is meant to do for us. We all discussed, inching closer together as we shared opinions on what art means. This led to us all sitting, talking, bitching, laughing, and scheming up ideas of hosting a performance and art event in a Fayetteville space. The evening serves as an example of how collaborations that bring forth creative community events are rarely successful without the trust that is facilitated by passionate, creative folks talking together and supporting each other in a welcoming space. Whether or not the events we envisioned will come to fruition, Stephanie’s home gave us the permission to dream up a project, to understand each other a little more, and to empathize with our struggles through these pandemic times. Simple conversation, then, becomes related to the openness created in the spaces Stephanie forms within her paintings, or the connections while performing her music with other people who are also fed up with injustice and inequality. Discussion in itself represents the unpretentious, yet purposeful, punk-rock approach conjured by simply being around the artist being around herself.